Experiment in Valverde de Burguillos-Badajoz-Spain

The story begins at the bottom of this page...

A história começa no fundo desta página...

La historia empeza abajo en esta página...

Die Geschichte beginnt ganz unten auf dieser Seite...

Reportaje en la Televisión Española / Spanish TV / Reportagen Televisiva Espanhola / Spanischer Fernsehbericht

Territorio Extremadura: Un proyecto experimental para conocer cómo se realizaban las estelas de guerreros

First results and comments on the quartzite stelae from Extremadura

On April 25, 2022, both stelae replications were finished and Alex left us with the slags and hopefully bloom from the furnance. We can finally state that the precondition for the making of the elaborate quartzite stelae with well-defined lines in Extremadura was the access to high quality, hardenable iron chisels. This means that the carbon-content was at least 0.45%. Such implements could have been produced locally with the methods used in this experiment, and we will definitely follow this track. We now have a terminus post quem for the making of these stelae (the introduction of iron technology), but no absolute date. The results from the analysis of the chisel from Rocha do Vigio confirm the availabilty of corresponding technologies or at least access to chisels (imports, local networks) from 900-800 BC onwards. The results of our research will soon be published in detail.

Resultados e comentários preliminares à estela quartzítica da Estremadura

A 25 de Abril de 2022 deram-se por concluídas as duas réplicas das estelas e o Alex deixou-nos a escória e, com sorte, também a escória de ferro da forja. É, finalmente, possível dizer que o pré-requisito para fazer as elaboradas estelas quartzíticas com linhas bem definidas na Estremadura seria ter acesso a escopros de ferro endurecível de elevada qualidade. Isto significa que o teor de carbono era pelo menos de 0.45%. Ferramentas desse tipo poderão ter sido produzidas localmente com os métodos usados nesta experiência, pelo que esse será o caminho que iremos definitivamente tomar. Temos agora um terminus post quem para o fabrico destas estelas (a introdução da tecnologia do ferro), ainda que sem datação absoluta. Os resultados da análise do escopro da Rocha do Vigio confirmam a existência de tecnologias correspondentes, ou, pelo menos, o acesso a escopros (importações, redes de contactos locais), a partir de 900-800 a.C.. Os resultados detalhados da nossa investigação serão publicados em breve.

Erste Ergebnisse zu den Quarzitstelen der Extremadura

Am 25. April 2022 waren beide Repliken fertig und Alex verliess uns mit der Schlacke und erhofften Luppe aus dem Ofen, um das Eisen herauszuarbeiten. Wir können feststellen, dass die Voraussetzung für alle exakt gearbeiteten Quarzitstelen der Extremadura der Zugang zu qualitativ hochwertigen, härtbaren Eisenmeisseln war. Dies bedeutet einen Kohlenstoffgehalt von mindestens 0,45%. Diese könnten mit den im Experiment verwendeten Methoden durchaus lokal hergestellt worden sein, wir werden diese Spur weiter verfolgen. Auf jeden Fall ergibt sich daraus ein Terminus post quem für die Herstellung der Stelen (nach der Einführung der Eisenverarbeitung), jedoch leider kein absolutes Datum. Die Analysenergebnisse des Meißels von Rocha do Vigio belegen entsprechende Technologien oder zumindest den Zugang (Import, lokale Netzwerke) ab ca. 900-800 v. u. Z. Unsere Forschungsergebnisse werden bald ausführlich publiziert.

(Foto: Ralph Araque)

Figure 23: Our stonemason Pepe with his results, the replication of Capilla 1, La Moraleja (right) and the interpretation of some motives from Capilla 8, La Pimenta (left).

Figura 23: Nuestro cantero Pepe con los resultados, la réplica de la Capilla 1, La Moraleja (derecha) y la interpretación de algunos motivos de la Capilla 8, La Pimenta (izquierda).

Figura 23: O nosso pedreiro Pepe com os resultados, a réplica de Capilla 1, La Moraleja (direita) e a interpretação de alguns motivos de Capilla 8, La Pimenta (esquerda).

Abbildung 23: Unser Steinmetz Pepe mit den Ergebnissen, der Replikation von Capilla 1, La Moraleja (rechts) und der Interpretation einiger Motive von Capilla 8, La Pimenta (links).

Video: Final Bronze Age or Early Iron Age Quality Iron in Action

9c7b5bb68d0b3d0954dae70490c1125c

Thanks to the Team from Canal Extremadura / Territorio Extremadura for the video!

Gracias / Obrigado al equipo de Canal Extremadura / Territorio Extremdaura por el video!

Figure 22: The Team from "Territorio Extremadura" from the station CANAL EXTREMADURA filmed and interviewed Pablo, Alex, Ralph and Pepe, who already had some routine from last time in Baraçal.

Figura 22: El equipo de "Territorio Extremadura" de la emisora CANAL EXTREMADURA filmó y entrevistó a Pablo, Alex, Ralph y Pepe, que ya tenían alguna rutina de la última vez en Baraçal.

Figura 22: A equipa do "Territorio Extremadura" da estação CANAL EXTREMADURA filmou e entrevistou Pablo, Alex, Ralph e Pepe, que já tinha alguma rotina da última vez em Baraçal.

Abbildung 22: Das Team der Sendung "Territorio Extremadura" vom CANAL EXTREMADURA filmte und interviewte Pablo, alex, Ralph und Pepe, der schon vom letzten Auftritt in Baraçal routiniert war.

El grabado y el picado de las líneas

Había llegado el momento de empezar con cincelar y grabar los motivos en las estelas. Nuestras piedras de cuarcita, una con superficie "hard ground" polido del río (La Pimenta) y un bloque con superficie un poco degradada estaban listas para el trabajo (La Moraleja). Afortunadamente no fue necesario tratar la superficie del cuarcita (como la del granito en el experimento en Baraçal), ya que era o lisa (hard ground) o fracturada de manera plana y más o menos lisa, constituyendo auténticas "lienzos naturales". Con nuestro concoimiento de las propriedades del cincel de Rocha do Vigio y la calidad del hierro de la época,esta parte del experimento era más fácil de lo que habíamos pensado al principio.

Gravando e picando as linhas

Finalmente, pudemos começar a parte artística, a gravação das estelas e a picagem dos motivos. Num caso, os nossos quartzitos tinham uma superfície perfeitamente uniforme, já que correspondiam geologicamente a terras duras carbonatas (ou “hard ground”), polidas pelo rio (La Pimenta). O outro bloco tinha uma superfície desgastada mas era de boa qualidade e muito uniforme e liso (La Moraleja). Felizmente, as rochas quartzíticas não necessitam de qualquer tratamento de superfície (como foi o caso do granito aplito na experiência do Baraçal), e constituem uma tela natural para desenhar. Graças ao nosso conhecimento do escopro da Rocha do Vigio e à elevada qualidade do ferro deste período, esta parte da experiência foi mais fácil do que julgámos.

Engraving and Picking the Lines

Finally, we could start with the artistic part, engraving the stelae and picking the motives. Our quartzites had an perfectly even surface in one case, as it was geologically "hard-ground" and polished by the river (La Pimenta). The other block had a weathered surface but was of good quality and very even and flat (La Moraleja). Fortunately, the quartzite rocks did not need any surface treatment (as it was the case with the granitic aplite in the experiment in Baraçal), and provided a natural screen for the designs. Thanks to our knowledge of the chisel from Rocha do Vigio and the high quality of the iron from this period, this part of the experiment was easier than we thought.

Gravieren und Picken der Linien

Endlich konnten wir anfangen, die Motive in die Stelen zu meisseln. Unsere Quarzite hatten in einem Fall eine perfekte, glatte Oberfläche, geologisch "hard ground", die zusätzlich vom Fluss poliert war (La Pimenta). Der andere Block hatte eine Verwitterungsschicht, unter der aber direkt eine gut bearbeitbare, flache und relativ ebene Bruchfläche lag. Zum Glück brauchte der Quarzit keine Oberflächenbearbeitung (wie der granitische Aplit im Experiment von Baraçal), denn er bietet in beiden Fällen eine natürliche "Leinwand". Mit unserem Wissen um den Meißel von Rocha do Vigio und die ausgezeicvhnete Qualität des damals verfügbaren Eisens war dieser Teil des Experimentes einfacher, als wir ursprünglich dachten.

(Foto: Ralph Araque)

Figure 18: The replicated iron chisel from Rocha do Vigio works surprisingly well for the carving of quartzite ...

Figura 18: El cincel de hierro replicado de Rocha do Vigio funciona sorprendentemente bien para la talla de cuarcita.

Figura 18: O cinzel de ferro replicado da Rocha do Vigio funciona surpreendentemente bem para a talha de quartzito.

Abbildung 18: Die Replik des Eisenmeissels von Rocha do Vigio funktioniert überraschend gut auf dem Quarzit ...

(Foto: Ralph Araque)

Figure 19: However, the chisel has to be frequently re-sharpened after a few minutes on the extremely hard rock...

Figura 19: Sin embargo, debido a la extrema dureza de la roca, hay que reafilar constantemente el cincel cada pocos minutos...

Figura 19: Contudo, com a rocha extremamente dura, o cinzel tem de ser constantemente re-aquecido de poucos em poucos minutos...

Abbildung 19: Allerdings muss der Meißel bei dem extrem harten Gestein ständig alle paar Minuten nachgeschärft werden...

(Fotos: Ralph Araque)

Figure 20: The tight lines on the stela from Capilla 1, La Moraleja can only have been realized with a sharp, accurate instrument.

Figura 20: Las apretadas líneas de la estela de la Capilla 1 de La Moraleja sólo pueden haberse realizado con un instrumento afilado y preciso.

Figura 20: As linhas apertadas na estela de Capilla 1, La Moraleja só podem ter sido realizadas com um instrumento afiado e preciso.

Abbildung 20: Die engen Linien von Capilla 1, La Moraleja konnten nur mit einem akkuraten, scharfen Werkzeug gehauen werden.

(Fotos: A Pablo Paniego Díaz, B Ralph Araque)

Figure 21: The traces of the iron chisel appear to be unambiguous: human figure on the weathered quartzite slab from Capilla 8, La Pimenta (A) and on our quatzite-pebble from Capilla.

Figura 21: Las huellas del cincel de hierro parecen ser inequívocas: figura humana en la losa de cuarcita meteorizada de Capilla 8, La Pimenta (A) y en nuestro guijarro de quatzita de Capilla.

Figura 21: Os vestígios do cinzel de ferro parecem ser inequívocos: figura humana na placa de quartzito desgastada de Capilla 8, La Pimenta (A) e na nossa folhagem de quartzito de Capilla.

Abbildung 21: Die Werkspuren des Eisenmeißels sind ziemlich eindeutig: Figur auf dem verwitterten Quarzitblock von Capilla 8, La Pimenta (A) und auf unserem Quarzitkiesel aus Capilla.

El perfilado de los motivos / Drawing the Design /

As previously known from our experiment in Baraçal, the next step for the stone mason was to transfer the design from the original stela from Capilla 1, La Moraleja, onto our rock that we had chosen for the replication. As we had only been able to obtain a significantly smaller block in Capilla (because my car would have broken down with any bigger stones in the back), we had to scale it a little smaller than on the original (ca. 80-90%). For the other, more interpretative stela based on Capilla 8, La Pimenta, it was possible to make a free hand drawing of the motives based on the photographs.

Projetando os Motivos

Tal como anteriormente, com a experiência do Baraçal, o passo seguinte para o artesão seria o de transferir o esquema decorativo da estela original de Capilla 1, La Moraleja, para a nossa rocha que escolhemos para a réplica. Uma vez que apenas conseguimos obter um bloco significativamente mais pequeno em Capilla (porque o carro teria avariado ao transportar quaisquer rochas maiores), tivemos de reduzir ligeiramente a escala da reprodução, tornando-a ca. 80-90% mais pequena que a original. Para a outra estela de maior interpretação baseada na de Capilla 8, La Pimenta, foi possível fazer à mão um desenho livre dos motivos, com base nas fotografias.

Anzeichnen der Motive

Wie bereits bei unserem Experiment in Baraçal war der nächste Schritt für den Steinmetz das Anzeichnen der Motive auf dem Stein für die Replik von Capilla 1, La Moraleja. Da wir nur einen deutlich kleineren Block als das Original transportieren konnten (weil mein Auto unter noch größeren Brocken zusammengebrochen wäre), mussten wir die Zeichnung etwas kleiner als das Original skalieren (ca. 80-90%). Bei der anderen, eher interpretativen Stele die auf Capilla 8, La Pimenta basiert, war es möglich, freihändig vom Foto abzuzeichnen, da wir nicht das absolute Maß an Genauigkeit beanspruchten.

(Fotos: Ralph Araque)

Figure 17: Drawing the design on the rock for the replication of Capilla 1, La Moraleja (left), after the original design had been blueprinted in the Museum of Badajoz (right).

Figura 17: Dibujando el diseño en la roca para la réplica de la Capilla 1, La Moraleja (izquierda), después de que el diseño original haya sido impreso en azul en el Museo de Badajoz (derecha).

Figura 17: Desenho na rocha para a replicação de Capilla 1, La Moraleja (esquerda), depois de o desenho original ter sido impresso em planta no Museu de Badajoz (direita).

Abbildung 17: Anzeichnen der Motive für die Replik von Capilla 1, La Moraleja (links), nachdem das Original-Design im Museum von Badajoz durchgepaust wurde (rechts).

Apresentação pública da “forja catalã” (ou “bloomery furnace”) e do processo de fundição à comunidade de Valverde

A 21 de Abril, o dia em que a forja estava pronta para queimar e fundir, convidámos a comunidade e vizinhos de Valverde para que se juntassem a nós e observassem o processo da fundição pré-histórica. Houve muito interesse e tivemos discussões científicas e engraçadas, bem como umas quantas cervejas que oferecemos para a ocasião. Da parte da tarde, o artesão demonstrou o efeito de diferentes ferramentas no quartzito, enquanto o ponto alto do entardecer foi a “morte” da forja.

Public presentation of the bloomery furnance and smelting for the community of Valverde

On April 21, the day when the furnace was ready to burn and smelt, we invited the village community and neighbours to join us and observe the process of prehistoric smelting. The interest was great and we had scientific as well as funny discussions, as well as a couple of beers that we offered for the occasion. In the afternoon, the stonemason showed the effect of different tools on quartzite, while the evening highlight was the final "slaughter" of the furnance.

Vorführung des Rennofens und Schmelzens für die BewohnerInnen von Valverde

Am 21. April, als der Rennofen bereit zum anheizen und schmelzen war, luden wir das Dorf und die Nachbarn ein, vorbeizukommen und sich den experimentell nachgestellten Prozess des prähistorischen Eisenausschmelzens anzuschauen. Es gab reges Interesse und es kam zu wissenschaftlichen sowie zu lustigen Diskussionen und Gesprächen bei ein paar Bier, die wir dem Publikum anboten. Nachmittags zeigte der Steinmetz den Effekt von verschiedenen Werkzeugen auf Quarzit. Der Abendhighlight war das "Schlachten" des Rennofens.

(Fotos: Obere Reihe: Roy Doberitz, untere: Ralph Araque)

Figure 15: We could present our experiment to a very interested audience in Valverde, some especially liked the tools (for sometimes unknown personal purposes) and others could contribute with their old knowledge of mining and coal-making.

Figura 15: Pudimos presentar nuestro experimento a un público muy interesado en Valverde, a algunos les gustaron especialmente las herramientas (con fines personales a veces desconocidos) y otros pudieron aportar sus antiguos conocimientos sobre minería y fabricación de carbón.

Figura 15: Poderíamos apresentar a nossa experiência a um público muito interessado em Valverde, alguns gostaram especialmente das ferramentas (para fins pessoais por vezes desconhecidos) e outros poderiam contribuir com os seus velhos conhecimentos sobre mineração e fabrico de carvão.

Abbildung 15: Wir konnten unser Experiment einem hochinteressierten Publikum in Valverde vorstellen. Manche fanden die Werkzeuge besonders spannend (mit manchmal eigenen Hintergedanken), andere konnten mit ihrem Wissen über alte Methoden des Bergbaus und der Köhlerei unser Wissen erweitern.

(Foto: Roy Doberitz)

Figure 16: The project team and the people of Valverde de Burguillos after the presentation on April 21, 2022.

Figura 16: El equipo del proyecto y el pueblo de Valverde de Burguillos tras la presentación del 21 de abril de 2022.

Figura 16: A equipa do projecto e o povo de Valverde de Burguillos após a apresentação a 21 de Abril de 2022.

Abbildung 21: Das Projektteam und die Dorfgemeinschaft von Valverde de Burguillos nach der Präsentation am 21. April 2022.

Fazendo uma “forja catalã” (ou “bloomery furnace”) e fundindo ferro a partir de minerais locais

A partir do momento em que reconhecemos a necessidade de escopros de ferro, começámos a adicionar uma nova fase à experiência: decidimos investigar se e como seria possível obter ferro a partir dos minérios locais através de uma forja catalã (Fig. 8). Esta é uma experiência ainda em curso, mas podemos já afirmar que a tecnologia encontrava-se principalmente disponível na Idade do Bronze Final. Existem dezenas de formas de garantir a ventilação necessária para obter a temperatura elevada que derrete o ferro, mas devido a restrições de ordem prática (tempo e dinheiro), nós usámos um soprador elétrico (Fig. 9). Abaixo descrevemos todo o processo, da produção do forno à destruição da forja e à recolha da escória de ferro (Fig. 10-11). Para todos os restantes resultados e análises do teor de carbono, etc., estamos ainda na fase experimental e os resultados serão publicados assim que tenhamos evidências conclusivas. Tudo o que podemos dizer para já é que as estelas começaram com a produção das ferramentas, ou mais concretamente, com a produção do carvão que garantia combustível à forja. Usámos 45 kg de “picón” (carvão de carvalho tradicional da Estremadura) para 15 kg de minério.

Making a bloomery (or renn) furnance and iron smelting from local minerals

Once we were aware of the fact that iron chisels were necessary, we started to add a new strand to the experiment: We decided to investigate if and how it was possible to obtain iron from local ores and minerals with a bloomery furnance (Fig. 8). This experimentation is still in course, but we can already state that the technology was principally available in the Final Bronze Age. There are dozens of ways to assure the ventilation that is needed to obtain the high temperature to melt iron, but out of practical restrictions (time and money) we used an electrically powered blower (Fig. 9). Below we describe the whole process from the making of the oven to the destruction of the furnance and the withdrawal of the bloomery (Fig. 10-11). For all further results and analyses of carbon content etc., we are still in the experimental phase and results will be published as soon as we have conclusive evidence. All we can say yet is that the stelae started with the making of the tools, or actually with the charcoal maker to provide combustible for the furnance. We used 45 kg of picón (traditional oak charcoal from Extremadura) for 15 kg of ore.

Der Bau eines Rennofens und das Ausschmelzen von Eisen aus lokalem Mineral

Da wir wussten, dass Eisenmeißel notwendig waren, begannen wir, das Experiment um einen neuen Strang zu erweitern: Wir beschlossen, zu untersuchen, ob und wie es möglich war, Eisen aus lokalen Erzen und Mineralien mit einem Rennofen zu gewinnen (Abb. 8). Diese Untersuchung ist noch nicht abgeschlossen, aber wir können schon jetzt sagen, dass diese Technologie bereits in der Spätbronzezeit zur Verfügung stand. Es gibt Dutzende von Möglichkeiten, die Belüftung zu gewährleisten, die notwendig ist, um die hohe Temperatur zum Schmelzen von Eisen zu erreichen, aber aus praktischen Gründen (Zeit und Geld) haben wir ein elektrisch betriebenes Gebläse verwendet (Fig. 9). Nachfolgend beschreiben wir den gesamten Prozess von der Herstellung des Ofens bis zur Zerstörung des Ofens und der Entnahme der Luppe (bzw. eisenhaltigen Schlacke) (Abb. 10-11). Für viele daraus folgenden Ergebnisse und Analysen des Kohlenstoffgehalts usw. befinden wir uns noch in der Versuchsphase, und die Ergebnisse werden veröffentlicht, sobald wir aussagekräftige Resultate haben. Alles, was wir jetzt schon sagen können, ist, dass die Stelen mit der Herstellung der Werkzeuge beginnen, oder eigentlich mit dem Köhler, der Brennmaterial für den Ofen herstellte. Wir haben 45 kg Picón (traditionelle Holzkohle aus Steineiche in der Extremadura) für 15 kg Erz verwendet.

(Fotos: Ralph Araque)

Figure 8: On two working days, Juan Monje (Taller Gremio) built a bloomery furnance in the traditional way from clay, loam and sand (secret recipe). A hole for the nozzle where the blower will be attached is built in. Thereafter, the furnance had to dry for at least two days, however usually better three or more days.

Figura 8: En dos días de trabajo, Juan Monje (Taller Gremio) construyó un horno de bloomery a la manera tradicional con arcilla, marga y arena (receta secreta). Se construyó un orificio para la boquilla donde se colocará el soplador. Después, el horno tenía que secarse durante al menos dos días, aunque normalmente es mejor tres o más días.

Figura 8: Em dois dias úteis, Juan Monje (Taller Gremio) construiu uma mobília florida à maneira tradicional a partir de argila e areia (receita secreta). É construído um buraco para o bocal onde o soprador será ligado. Posteriormente, o mobiliário teve de secar durante pelo menos dois dias, no entanto, geralmente melhor três ou mais dias.

Abbildung 8: An zwei Arbeitstagen baut Juan Monje (Taller Gremio) den Rennofen auf traditionelle Art aus Ton, Lehm, und Sand (Geheimrezeptur). Ein Loch für die Keramikdüse, an die das Gebläse angeschlossen wird, wurde eingebaut. Danach musste der Ofen für mindestens zwei Tage trocknen, besser aber wären drei oder mehr Tage.

(Fotos: Ralph Araque)

Figure 9: The blower, the burning furnance and Alex adjusting the system on April 21.

Figura 9: El ventilador, el horno encendido y Alex ajustando el sistema el 21 de abril.

Figura 9: O ventilador, o forno a arder e o Alex a ajustar o sistema a 21 de Abril.

Abbildung 9: Das Gebläse, der brennende Ofen und Alex beim ausrichten der Konstruktion am 21. April.

(Fotos: Ralph Araque)

Figure 10: From top to bottom: The furnance is fired and filled with layers of charcoal and iron minerals for at least 6 hours (better would have been much longer). At some stage, it can be helpful to drain slags, but we had none coming out. Finally, the furnance is detroyed to get to its contents...

Figura 10: De arriba a abajo: El horno se cuece y se llena de capas de carbón vegetal y minerales de hierro durante al menos 6 horas (mejor hubiera sido mucho más tiempo). En algún momento, puede ser útil escurrir las escorias, pero a nosotros no nos salió ninguna. Por último, se destruye el horno para llegar a su contenido...

Figura 10: De cima para baixo: O mobiliário é queimado e preenchido com camadas de carvão vegetal e minerais de ferro durante pelo menos 6 horas (melhor teria sido muito mais tempo). A dada altura, pode ser útil drenar escórias, mas não tivemos nenhuma a sair. Finalmente, o mobiliário é detroyed para chegar ao seu conteúdo...

Abbildung 10: Von oben nach unten: Der Rennofen wird befeuert und abwechselnd werden Schichten von Kohle und gepochtem Eisenmineral eingefüllt. Zwischendrin kann es hilfreich sein, die Schlacke abzulassen (aber wir hatten nicht so viel flüssige davon). Am Ende wird der Rennfen geschlachtet, um an den Inhalt zu kommen...

(Fotos: Ralph Araque)

Figure 11: ... the rest of the bloomery furnance the next day and the "bloomery", mainly consisting of slags, rests of charcoal and ceramic fragments, and, hopefully, some pure iron. It has to be cleared in the forge.

Figura 11: ... el resto del horno de la bloomería al día siguiente y la lupia, compuesta principalmente por escorias, restos de carbón y fragmentos de cerámica y, con suerte, algo de hierro puro. Hay que limpiarlo en la fragua.

Figura 11: ... o resto do mobiliário florido no dia seguinte e a "lupia", constituída principalmente por escórias, restos de carvão vegetal e fragmentos de cerâmica, e, espera-se, algum ferro puro. Tem de ser limpo na forja.

Abbildung 11: ... der Rest des Ofens und die "Luppen", die in unserem Fall hauptsächlich aus Schlacke, etwas Holzkohleresten und Keramikbruchstücken und, hoffentlich, etwas reinem Eisen bestehen. dies muss in der Schmiede gereinigt werden.

How do we do with the iron ore or minerals?

The area of Valverde is extraordinarily rich in iron ores and minerals, there are some famous and some less known abandoned mines around. We obtained ours from a nearby site, where it had theoretically always been available on the surface (Fig. 12).

¿Qué hacemos con el mineral de hierro o los minerales?

La zona de Valverde es extraordinariamente rica en minerales de hierro, hay algunas minas abandonadas famosas y otras menos conocidas en los alrededores. Nosotros obtuvimos el nuestro de un yacimiento cercano, donde teóricamente siempre había estado disponible en la superficie (Fig. 12).

Como fazemos com o minério de ferro ou minerais?

A área de Valverde é extraordinariamente rica em minérios e minerais de ferro, existem algumas minas famosas e algumas menos conhecidas abandonadas em redor. Obtivemos a nossa de um local próximo, onde teoricamente sempre esteve disponível na superfície (Fig. 12).

Wie verfahren wir mit dem Erz bzw. eisenhaltigen Mineral?

Die Gegend von Valverde ist außerordentlich reich an Eisenerzen und -mineralen und es gibt einige bekanntere und unbekannte aufgegeben Minen in der Umgebung. Wir haben unsere Steine bei einer nahegelegenen Mine besorgt, wo sie theoretisch auch schon immer an der Oberfläche vorkamen (Abb. 12).

(Fotos: Ralph Araque and Giuseppe Vintrici)

Figure 12: The monument for the nearby mine of Burguillos del Cerro, now a national cultural heritage site. We inspected an abandoned shaft of a smaller mine, where there was no ore left; in the surroundings, we found good quality minerals from the old mining activities. The characteristic black rocks come to the surface, now between the cattle that is grazing in the area.

Figura 12: El monumento de la cercana mina de Burguillos del Cerro, ahora patrimonio cultural nacional. Inspeccionamos un pozo abandonado de una mina más pequeña, donde no quedaba mineral; en los alrededores, encontramos minerales de buena calidad procedentes de las antiguas actividades mineras. Las características rocas negras salen a la superficie, ahora entre el ganado que pasta en la zona.

Figura 12: O monumento da mina vizinha de Burguillos del Cerro, agora património cultural nacional. Inspeccionámos um poço abandonado de uma mina mais pequena, onde já não havia minério; nos arredores, encontrámos minerais de boa qualidade provenientes das antigas actividades mineiras. As rochas negras características vêm à superfície, agora entre o gado que está a pastar na zona.

Abbildung 12: Denkmal für die nahegelegene Mine von Burguillos del Cerro, heute ein geschütztes Kulturerbe; Wir inspizierten den Schacht einer kleineren Mine, dort war kein Mineral übrig; in der Umgebung fanden wir noch gut brauchbares Material auf den Halden; die charakteristischen schwarzen Felsen kommen bis an die Oberfläche, wo jetzt nur noch Kühe grasen.

(Foto: Ralph Araque)

Figure 13: First, the stones have to be toasted in the fire for several hours, until they become brittle, otherwise they are useless.

Figura 13: Primero hay que tostar las piedras en el fuego durante varias horas, hasta que se vuelvan quebradizas, de lo contrario no sirven.

Figura 13: Primeiro, as pedras têm de ser tostadas no fogo durante várias horas, até se tornarem quebradiças, caso contrário são inúteis.

Figure 13: Zuerst müssen die Steine mehrere Stunden im Feuer geröstet werden, bis sie spröde werden, sonst sind sie nutzlos.

(Fotos: Ralph Araque)

Figure 14: After toasting, the mineral has to be pounded to fingernail-size, which is a lot of work. The same has to be done with copper minerals, hence people in the final Bronze Age were used to this procedure.

Figura 14: Después de tostar el mineral, hay que machacarlo hasta dejarlo del tamaño de una uña, lo que supone mucho trabajo. Lo mismo hay que hacer con los minerales de cobre, de ahí que la gente de la última Edad de Bronce estuviera acostumbrada a este procedimiento.

Figura 14: Depois de torrado, o mineral tem de ser esmagado até ao tamanho de uma unha, o que é muito trabalho. O mesmo tem de ser feito com minerais de cobre, daí que as pessoas na Idade do Bronze final estivessem habituadas a este procedimento.

Abbildung 14: nach dem Rösten muss das Mineral gepocht werden, d.h. auf Fingernagelgröße zerkleinert, und dass ist viel Arbeit. Das gleiche gilt übrigens auch für Kupferminerale, die Menschen der Spätbronzezeit waren das also gewöhnt.

Finding the right tool

Quartzite is one of the hardest stones for carving ornaments; this has been true back in the Bronze Age as it is today. Most stonemasons are not happy when confronted with this task. Fortunately, we had found and analysed the iron chisel from Rocha do Vigio in February. The findspot in Portugal is not far (just over the river Guadiana) from Valverde de Burguillos... Since the analyses revealed a surprisingly high carbon content and therefore an advanced iron technology, we had a trump in our hand. Alex Richter, a blacksmith from Sevilla, made us three replications corresponding to Bastian Asmus' findings in the analyses (Fig. 6). For the experiment, we tried to harden a chisel in a campfire, however we could not obtain an appropriate temperature for perfect hardening (Fig. 7). Nevertheless, in a furnance as it had been used by Bastian Asmus in Baraçal, this would have definitely been possible. The only difference in the hardening process is that bronze is first quenched, then hammered, while with iron is the reverse.

Encontrar la herramienta adecuada

La cuarcita es una de las piedras más duras para tallar ornamentos; esto era cierto tanto en la Edad de Bronce como en la actualidad. La mayoría de los canteros no están contentos cuando se enfrentan a esta tarea. Afortunadamente, en febrero encontramos y analizamos el cincel de hierro de Rocha do Vigio. El lugar del hallazgo, en Portugal, no está lejos (justo al otro lado del río Guadiana) de Valverde de Burguillos... Como los análisis revelaron un contenido de carbono sorprendentemente alto y, por tanto, una tecnología de hierro avanzada, teníamos un as en la manga. Alex Richter, un herrero de Sevilla, nos hizo tres réplicas correspondientes a los hallazgos de Bastian Asmus en los análisis (Fig. 6). Para el experimento, intentamos endurecer un cincel en una hoguera, sin embargo no pudimos obtener una temperatura adecuada para un endurecimiento perfecto (Fig. 7). Sin embargo, en un horno como el utilizado por Bastian Asmus en Baraçal, esto habría sido definitivamente posible. La única diferencia en el proceso de endurecimiento es que el bronce se enfría primero y luego se martillea, mientras que con el hierro ocurre lo contrario.

Encontrar a ferramenta certa

Quartzito é uma das rochas mais duras para talhar esquemas decorativos; isto era tão verdade na Idade do Bronze como o é hoje. A maioria dos artesãos não gostam dessa tarefa. Felizmente, nós tínhamos encontrado e analisado o escopro de ferro da Rocha do Vigio em Fevereiro. O local de achado em Portugal não é muito longe de Valverde de Burguillos... Uma vez que as análises revelaram um teor de carbono surpreendentemente elevado e, portanto, uma tecnologia avançada de ferro, tínhamos um trunfo nas mãos. Alex Richter, um ferreiro de Sevilha, fez-nos três réplicas correspondentes aos resultados das análises de Bastian Asmus (Fig. 6). Para a experiência, tentámos endurecer um escopro numa fogueira, contudo não foi possível obter a temperatura adequada para o endurecimento perfeito (Fig. 7). Não obstante, numa forja como a que foi usada pelo Bastian Asmus no Baraçal, isto teria definitivamente sido possível. A única diferença no processo de endurecimento é que o bronze é primeiramente apagado e posteriormente martelado, enquanto o ferro é o contrário.

Werkszeugsuche

Quarzit ist einer der härtesten Werksteine für Ornamentik, damals wie heute. Die meisten Steinmetze sind wenig begeistert von dieser Arbeit. Zum Glück hatten wir im Februar den Meißel von Rocha do Vigio analysiert, der Fundort in Portugal ist nicht weit von Valverde de Burguillos (über den Fluß Guadiana)... Da die Analysen einen überrschend hohen Kohlenstoffanteil zeigten, hatten wir einen Trumpf in der Hand. Alex Richter, Schmied aus Sevilla, fertigte uns drei Repliken an, deren Kohlenstoffgehalt auf Bastian Asmus' Analysen beruht (Abb. 6). Beim Experiment versuchten wir auch, den Meißel vor Ort im Feuer zu härten, allerdings erreichten wir nicht die benötigte Temperatur (Abb. 7). Diese wäre aber ohne weiteres in einem Ofen, wie ihn Bastian Asmus in Baraçal gebaut hat, möglich gewesen.

(Fotos: Ralph Araque)

Figure 6: Alex the blacksmith is happy that his replication of the chisel from Rocha do Vigio, using the same carbon concentration in the steel as in the protohistoric original and hardening them with the traditional process, do acftually work very well on the quartzite. Three replications and a modern hammer, back in the day the stonemasons would most probably have used bronze hammers of the same shape and weight, or wooden mallets.

Figura 6: Alex el herrero está contento de que su réplica del cincel de Rocha do Vigio, utilizando la misma concentración de carbono en el acero que en el original protohistórico y endureciéndolos con el proceso tradicional, funcionen realmente muy bien en la cuarcita. Tres réplicas y un martillo moderno, en su día los canteros probablemente habrían utilizado martillos de bronce de la misma forma y peso, o mazos de madera.

Figura 6: Alex, o ferreiro, está feliz por a sua replicação do cinzel da Rocha do Vigio, usando a mesma concentração de carbono no aço que no proto-histórico original e endurecendo-os com o processo tradicional, funcionar de facto muito bem no quartzito. Três réplicas e um martelo moderno, antigamente os pedreiros teriam muito provavelmente utilizado martelos de bronze com a mesma forma e peso, ou martelos de madeira.

Abbildung 6: Alex der Schmied ist glücklich, dass seine Repliken des Meißels von Rocha do Vigio, bei denen er Stahl mit dem selben Kohlenstoff-Gehalt wie das prähistorische Original benutzte und diesen traditionell gehärtet hat, tatsächlich so gut auf dem Quartzit funktioniert. Rechts die drei Repliken und ein moderner Fäustel, damals hätten die Steinmetze wohl Bronzefäustel (mit ähnlichem Gewicht) oder Holzklüpfel benutzt.

(Fotos: Ralph Araque)

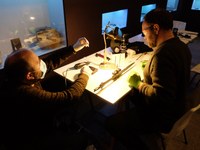

Figure 7: The blacksmith explains the hardening process of his chisel. As the right temperature is visible in the colour of the hot iron (orange), it can only be done at night or in darkness. Unfortunately, our campfire only reached ca. 800 degrees celsius, giving it a cherry-red colour, and hardening was only halfway successful. After hammering, the chisel has to be quenched in cool water.

Figura 7: El herrero explica el proceso de endurecimiento de su cincel. Como la temperatura adecuada es visible en el color del hierro caliente (naranja), sólo puede hacerse de noche o en la oscuridad. Desgraciadamente, nuestra hoguera sólo alcanzaba unos 800 grados centígrados, lo que le daba un color rojo cereza, y el endurecimiento sólo se conseguía a medias. Tras el martilleo, el cincel debe enfriarse en agua fría.

Figura 7: O ferreiro explica o processo de endurecimento do seu cinzel. Como a temperatura correcta é visível na cor do ferro quente (laranja), só pode ser feita à noite ou na escuridão. Infelizmente, a nossa fogueira só atingiu ca. 800 graus celsius, dando-lhe uma cor vermelho cereja, e o endurecimento só teve metade do sucesso. Depois de martelar, o cinzel tem de ser extinto em água fria.

Abbildung 7: Der Schmied erklärt den Härtungsprozess für den Meißel. Da die richtige Temperatur über die Farbe des glühenden Esiens erkannt wird, kann der Prozess nur nachts oder in der Dunkelheit durchgeführt werden. Leider hat unser Lagerfeuer nur ca. 800 Grad Celsius erreicht, was dem Eisen eine kirschrote Farbe gibt, und das Härten war nur halbwegs erfolgreich. Nach dem Hämmern des glühenden Eisens werden die Meißel in kaltem Wasser abgeschreckt.

Las Herramientas tradicionales del Bronce Final / The traditional tools available in the Late Bronze Age / Die traditionellen Werkzeuge der späten Bronzezeit

(Foto: Giuseppe Vintrici)

Figure 4: The workbench and the "standard Bronze Age" set of tools from the stonemason's point of view: quartzite hammers from Michael Kaiser, lithic tools corresponding to our favourite from Portugal (Tool 15) and bronze chisels with grinding stone.

Figura 4: El banco de trabajo y el conjunto de herramientas "estándar de la Edad del Bronce" desde el punto de vista del cantero: martillos de cuarcita de Michael Kaiser, herramientas líticas correspondientes a nuestra favorita de Portugal (herramienta 15) y cinceles de bronce con piedra de afilar.

Figura 4: A bancada de trabalho e o conjunto de ferramentas da "Idade do Bronze padrão" do ponto de vista do pedreiro: martelos de quartzito de Michael Kaiser, ferramentas líticas correspondentes ao nosso favorito de Portugal (Ferramenta 15) e cinzéis de bronze com pedra de amolar.

Abbildung 4: Die Werkbank und das "Standard-Bronzezeit-Set" Werkzeuge: Quarzithämmer von Michael Kaiser, Steinwerkzeuge, die unserem Lieblingsklopfer aus Portugal (Tool 15) entsprechen, und Bronzemeissel mit Schleifstein.

(Fotos: Roy Doberitz except bottom left: Ralph Araque)

Figure 5: After testing the different tools it became clear: there can only be one... Except for the iron chisel, none of the other available tools can carve such precise lines as they are visible on many quartzite stelae. The stone tool could at least have been used for irregular, inaccurate, superficial and broad lines as they are also visible on some stelae, if someone would have invested considerable time and effort. The quartzite hammer splinters rapidly and the bronze chisels just bounce off (see video) or break.

Figura 5: Después de probar las diferentes herramientas quedó claro: sólo puede haber una... Salvo el cincel de hierro, ninguna de las otras herramientas disponibles puede tallar líneas tan precisas como las que son visibles en muchas estelas de cuarcita. La herramienta de piedra podría haber servido al menos para trazar líneas irregulares, imprecisas, superficiales y anchas como las que también son visibles en algunas estelas, si alguien hubiera invertido un tiempo y un esfuerzo considerables. El martillo de cuarcita se astilla rápidamente y los cinceles de bronce simplemente rebotan (ver vídeo) o se rompen.

Figura 5: Depois de testar as diferentes ferramentas, tornou-se claro: só pode haver uma... Excepto no cinzel de ferro, nenhuma das outras ferramentas disponíveis pode esculpir linhas tão precisas como são visíveis em muitas estelas de quartzito. A ferramenta de pedra poderia pelo menos ter sido utilizada para linhas irregulares, imprecisas, superficiais e largas como também são visíveis em algumas estelas, se alguém tivesse investido tempo e esforço consideráveis. O martelo de quartzito estilhaça rapidamente e os cinzéis de bronze simplesmente saltam (ver vídeo) ou partem-se.

Abbildung 5: Beim Werkzeugtest wird klar: es kann nur Einen geben... Ausser der Eisenmeißel-Replik funktioniert keines der anderen Werkzeuge, zumindest nicht für präzise Linien, wie sie auf vielen Quarzitstelen zu sehen sind. Das Steinwerkzeug wäre immerhin für ungenaue, breite Linien geeignet, wie sie auf ein paar anderen Stelen zu sehen sind, und wenn mensch sich sehr viel Zeit dafür nimmt. Der Quarzithammer splittert schnell, die Bronzemeißel prallen einfach ab (s. Video) oder gehen kaputt.

Video: Bouncing bronze chisels on quartzite / Cincel de bronze rebotando en cuarcita / Abprallender Bronzemeißel auf Quarzit

69f7dc9b82e33f0a4aa94dd42bd06f13

(Video: Roy Doberitz)

Bronze chisels with 12, 14 and 16 % tin alloys bouncing and splintering when trying them on quartzite.

Los cinceles de bronce con aleaciones de estaño del 12, 14 y 16 % rebotan y se astillan al probarlos en cuarcita.

Cinzéis de bronze com 12, 14 e 16 % de ligas de estanho a saltar e a estilhaçar ao experimentá-las em quartzito.

Bronzemeißel mit 12, 14 und 16% Zinngehalt in der Legierung prallen ab und splittern auf dem Quarzit.

Figure 3: The community of Valverde de Burguillos and the mayor Carlos greatly supported our work and offered us a workshop in a ruined building next to their brand new lodging facilities for research teams in the area, we were the first guests! Muchisimas gracias for the amazing hospitality !!!

Figura 3: La comunidad de Valverde de Burguillos y el alcalde Carlos apoyaron enormemente nuestro trabajo y nos ofrecieron un taller en un edificio en ruinas junto a sus flamantes instalaciones de alojamiento para equipos de investigación en la zona, ¡fuimos los primeros invitados! ¡¡¡Muchisimas gracias por la increíble hospitalidad !!!

Figura 3: A comunidade de Valverde de Burguillos e o presidente da câmara Carlos apoiaram grandemente o nosso trabalho e ofereceram-nos um workshop num edifício em ruínas junto às suas novas instalações de alojamento para equipas de investigação na área, fomos os primeiros convidados! Muchisimas gracias pela fantástica hospitalidade!!!

Abbildung 3: Die Gemeinde von Valverde de Burguillos und der Bürgermeister Carlos unterstützten unsere Arbeit großartig und stellten uns eine Werkstatt in einerm, alten Gemäuer neben ihrer brandneuen Herberge für Forscherteams zur Verfügung, wir waren die ersten Gäste! Muchisimas gracias für die rieseige Gastfreundschaft !!!

Let's get to work! Our candidates for replication and the search for suitable stones

On April 14, we started with a thorough inspection and work-trace analysis of the original stelae in the Museum of Badajoz (Fig. 1), while the geologist was analysing the rocks for their composition provenancing (link). Two days later, on April 16, we drove 250 km (each way!) to the outcrops of quartzite in Capilla (Fig. 2). Around the water reservoir, 14 stelae, including our two candidates for replication have been found, most of them from quartzite. There, we chose and loaded two quartzite slabs into the Volvo and brought them to our workshop in Valverde.

¡Manos a la obra! Los modelos de nuestras réplicas y la búsqueda de las piedras apropiadas

El 14 de Abril comenzamos con un examen minucioso de las piezas en el Museo de Badajoz (imagen 1) y la inspección de los rastros que había dejado el tallado de la piedra, mientras el geológo estaba analisando la composición de las piedras. Dos dias despues, el 16 de Abril, fuimos a 250 km (cada camino!) a los afloramientos de cuarcita de Capilla, donde se encontraban 14 estelas alrededor del embalme, incluyendo los dos cuales hemos escogido para replicar (imagen 2). Alli, seleccionamos y cargamos dos bloques en el Volvo y los llevamos al taller en Valverde.

Vamos ao trabalho! As nossas candidatas a réplicas e a procura por rochas adequadas

A 14 de Abril, começámos com uma inspeção minuciosa e uma análise à proveniência das estelas originais no Museu de Badajoz (Fig. 1), enquanto o geólogo analisava as rochas pela proveniência da sua composição . Dois dias depois, a 16 de Abril, viajámos 250 km (em ambas as direções!) até aos afloramentos de quartzito em Capilla (Fig. 2). Em torno da reserva de água, 14 estelas, incluindo as nossas duas candidatas a réplicas, tinham sido encontradas, na sua maioria de quartzite. Ali, escolhemos duas lajes quartzíticas, carregámo-las no Volvo e trouxemo-las para a nossa oficina em Valverde.

An die Arbeit! Die Vorbilder unserer Repliken und die Suche nach passenden Steinen

Am 14. April begannen wir mit einer ausführlichen Inspektion und Werkspurenanalyse bei den Originalen im Museum von Badajoz (Abb. 1).Zwei Tage später, am 16. April, fuhren wir 250 km (pro Strecke) zu den Quarzit-Lagerstätten von Capilla, wo um einen Stausee herum allein 14 Stelen gefunden wurden, die meisten aus Quarzit und darunter unsere beiden Vorbilder (Abb. 2). Dort wählten wir zwei Steine aus und luden sie in den Volvo, um sie nach Valverde in die Werkstatt zu bringen.

(Fotos: Pablo Paniego Díaz)

Figure 1: Original stelae from Capilla 1, La Moraleja (Left) and Capilla 8, La Pimenta (right). Both made from local quartzite.

Figura 1: Estelas originales de la Capilla 1, La Moraleja (izquierda) y de la Capilla 8, La Pimenta (derecha). Ambas hechas con cuarcita local.

Figura 1: Estela original de Capilla 1, La Moraleja (esquerda) e Capilla 8, La Pimenta (direita). Ambos feitos a partir de quartzito local.

Abbildung 1: Die Original-stelen von Capilla 1, La Moraleja (links), und Capilla 8, La Pimenta (rechts). Beide aus lokalem Quarzit.

(Fotos: upper Pedro Baptista, lower Ralph Araque)

Figure 2: The fractured quartzite rocks near the Capilla reservoir (bottom right, with the quartzite mountain range of Cabeza del Buey). We tried with a crowbar to obtain a slab - according to all Bronze Age health and safety standards - but without massive tools, the rock was too hard. We had to pick two rocks that were already scattered on the field.

Figura 2: Las rocas de cuarcita fracturadas cerca del embalse de Capilla (abajo a la derecha, con la sierra de cuarcita de Cabeza del Buey). Intentamos con una palanca obtener una losa -según todas las normas de seguridad e higiene de la Edad de Bronce- pero sin herramientas masivas, la roca era demasiado dura. Tuvimos que coger dos rocas que ya estaban esparcidas por el campo.

Figura 2: As rochas quartzíticas fracturadas perto do reservatório de Capilla (em baixo à direita, com a cordilheira quartzítica de Cabeza del Buey). Tentámos com um pé-de-cabra obter uma laje - de acordo com todas as normas de saúde e segurança da Idade do Bronze - mas sem ferramentas maciças, a rocha era demasiado dura. Tivemos de escolher duas rochas que já estavam espalhadas no campo.

Abbildung 2: Die geklüfteten Quarzitfelswände von Capilla neben dem Stausee (unten links, mit der Quarzit-Gebirgskette von Cabeza del Buey im Hintergrund). Wir versuchten mit dem Brecheisen, eine Platte - gemäß aller Bronzezeitlichen Sicherheitsvorschriften - herauszubrechen, aber ohne massive Werkzeuge war der Fels zu hart. Wir mußten zwei Steine mitnehmen, die schon auf dem Feld lagen.